Practical Data Science

Learning Paradigms

Beyond the usual training of neural networks, there are few major learning variants:

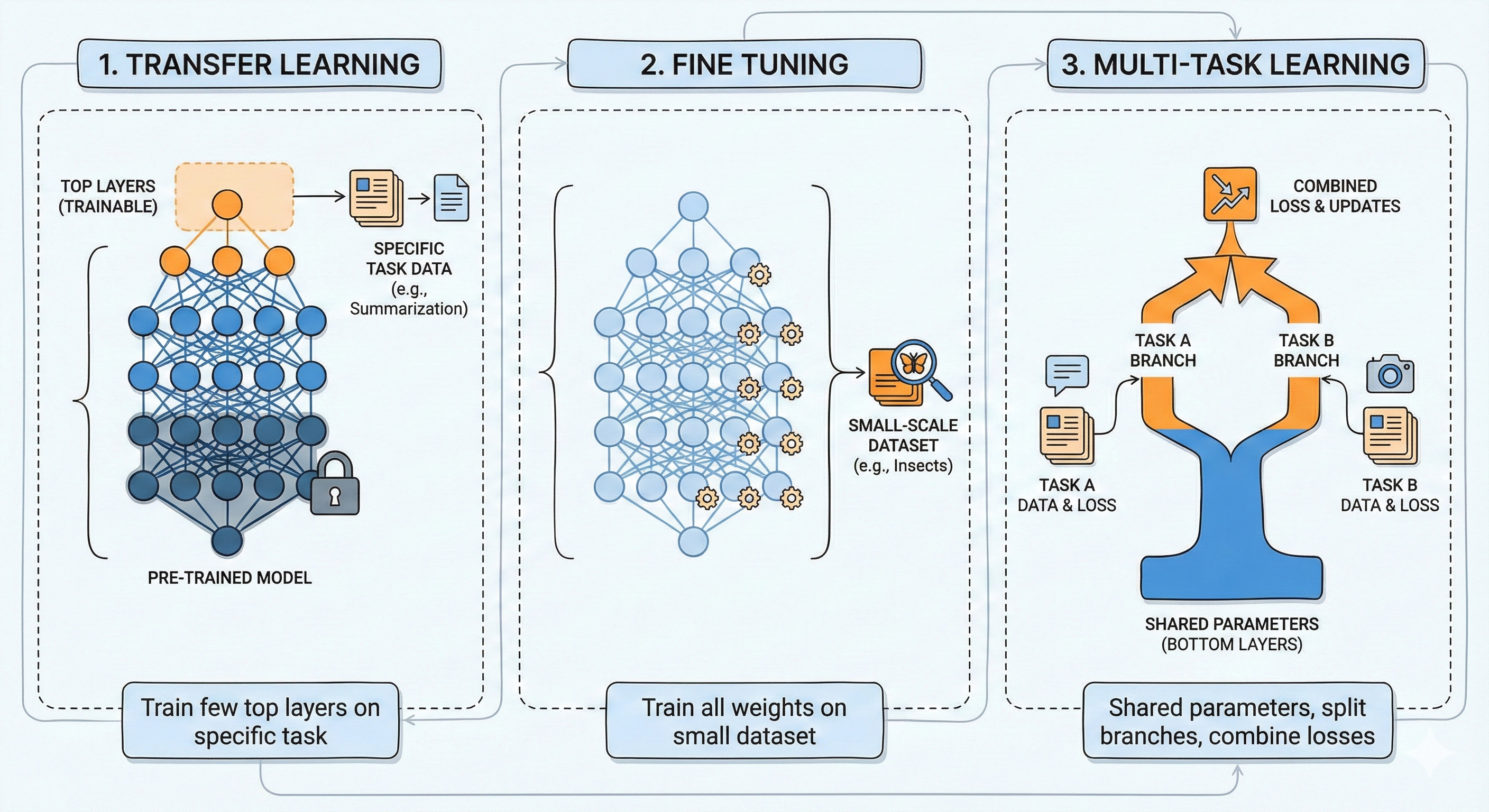

Transfer Learning: Here, you take a pre-trained model, and train only a few top layers to ensure that it adapts to the specific tasks. For example, a pre-trained model capable to comprehension of English language, could be used via transfer learning to summarize paragraphs, or for question-answering.

Fine tuning: Again we take a pretrained model, but train all the weights (or parameters) but only for a small scale dataset (less number of epoch) to make it adhere to the nuisances of that dataset. A pre-trained large image classification model can be fine-tuned to classify between different types of insects and their species, which may be useful for a group of entomologists.

Multi-task Learning: Here, we take atleast two different tasks, and we want to keep the idea of shared parameters like transfer learning. But, instead of training for one task at a time, we combine the losses arising from two different tasks, and then train the entire network (like fine tuning). The network architecture looks like it has a few shared parameter at the bottom layers, but suddenly it splits off into branches, each adapted to a specific task, and uses different parameters and different set of top layers.

Additionally, there are also different variants that are emerging due to specific needs.

- Federated Learning:

- Modern devices like mobiles and other IoT devices collects lots of data. But most of these data are private.

- Due to privacy concerns, the ML model training cannot use whole of the data as they do not remain in a central place.

- Instead of bringing the data to the models, we bring the model to the data.

- Each IoT device downloads a part of the model, trains it on the private data by computing a few gradient steps, and send back to server.

- The server aggregates the gradient steps from billions of users, and updates the entire model from an aggregated source of data.

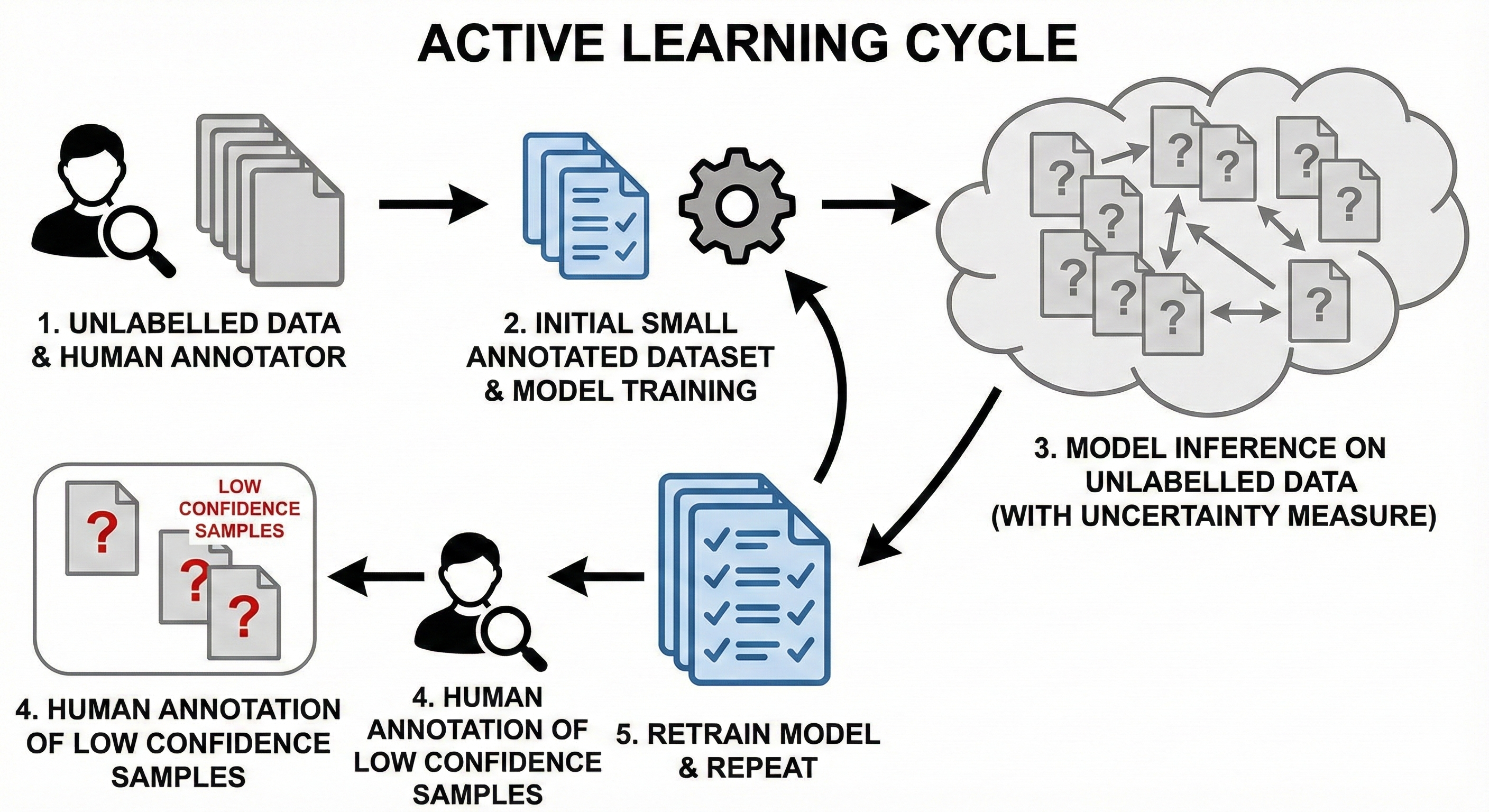

- Active Learning:

- Suppose we want to build a supervised system, but we do not have a training data with labels, only unlabelled data is present.

- This means, we need to build the system step-by-step where each step should ideally improve the model.

- Active Learning refers to a paradigm where the sampling is done simulteneously with model training. What this means is the following:

- Start with a small human annotated datasets. Large part of the data remains unlabelled.

- Train a model using that annotated part. We understand that this model is going to be inaccurate. Let it be. Also create some sort of uncertainty measure.

- Use the model to predict the labels / make inference on rest of the dataset, along with confidence level.

- Whichever samples have low confidence level, for them, ask the human annotator to label them.

- Retrain the model on this new dataset.

- While combining the low-confidence data with the seed data, we can also use the high-confidence data. The labels would be the model’s predictions. This variant of active learning is called “Co-operative learning”.

Training Techniques

Cost of Training Large Models

Let us ask the question:

How much memory does it take to train a \(n\) billion parameter model?

The key trick is to remember this approximate conversion table:

\(10^3\) bytes = 1 thousand bytes = 1 KB

\(10^6\) bytes = 1 million bytes = 1 MB

\(10^9\) bytes = 1 billion bytes = 1 GB

Let us now look at the amount of storage we need:

If each parameter has

float16representation, they take 16 bits or 2 bytes. Hence, we need \(2n\) billion bytes or \(2n\) GB of RAM to load the model.If we are training, each parameter will have its own gradient value that we need to store, resulting in another \(2n\) GB of storage.

If we use Adam optimizer, then we have a formula like:

\[ \hat{\theta}^{(t+1)} = \hat{\theta}^{(t)} - \alpha \frac{\partial L}{\partial \theta}\vert_{\theta = \hat{\theta}^{(t)}} + \beta \frac{m_t}{\sqrt{v_t}} \]

These \(m_t\) and \(v_t\) are momentum and variance parameters, and since we are doing division and taking square roots, we will need more precision for them. Standard is to use float32 for these variables. Hence, storing momentum requires \(4n\) GB, and so is variance.

Together we need \((2 + 2 + 4 + 4)n = 12n\) GB of storage for full-precision training. But for testing, we need only \(2n\) GB of storage.

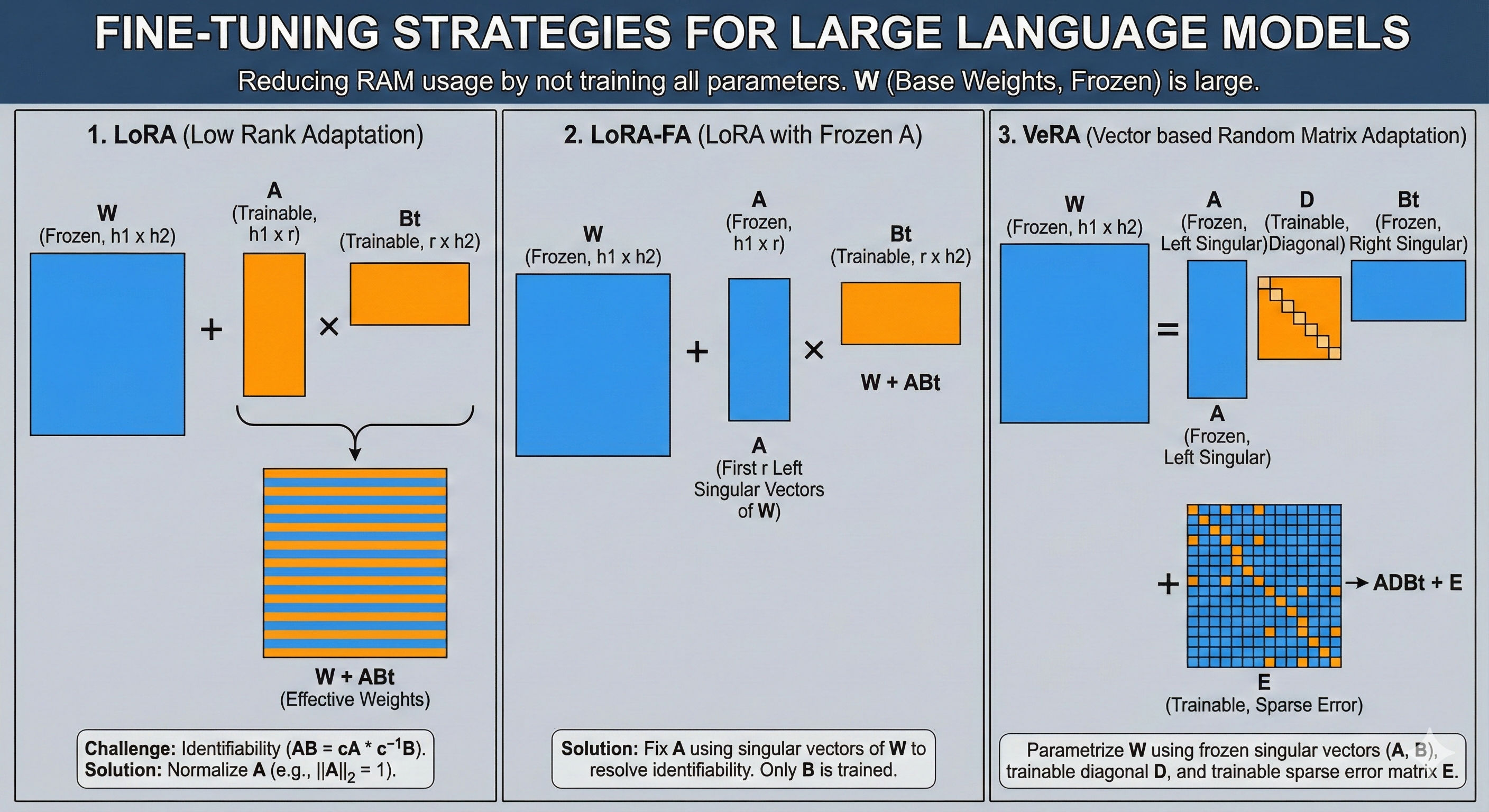

Fine-tuning Strategies for Large Language Models

There have been proposals of various fine-tuning strategies for large language models, that does not require the whole \(12n\) GB of storage in your RAM.

- LoRA: LoRA (Low Rank Adaptation) is a fine-tuning technique where instead of modifying the parameters (or weights) for the LLM directly, we add a low-rank adjustment on top of it. Say, at a particular layer of the large language model, we need a trainable weights \(W\) of dimensions \(h_1 \times h_2\), where \(h_1\) and \(h_2\) are large. Then, with the fine-tuning, we replace it by \[ W + AB^t \]

where \(A\) is of dimension \(h_1 \times r\) and \(B\) is of dimension \(r \times h_2\) and \(r\) is a much smaller number than \(h_1\) and \(h_2\). The matrices \(A\) and \(B\) are trainable.

A challenge is that both the matrices \(A\) and \(B\) are not identifiable, for example, \(AB = cA \times c^{-1}B\) for any \(c \neq 0\). Usually, to avoid this, one approach is to always keep the \(A\) matrix normalized so that \(||A||_2 = 1\).

LoRA-FA: LoRA with Frozen A. In this case, to avoid the identifiability issue, one may take \(A\) to be fixed as the matrix comprising of first \(r\) left singular vectors of \(W\) corresponding to the largest (in magnitude) \(r\) singular values of \(W\). Then, only the matrix \(B\) is trained.

VeRA: VeRA (Vector based Random Matrix Adaptation) is a technique where we parametrize the weight matrix \(W\) as

\[ W = ADB^t + E \]

where \(A\) and \(B\) are the top \(r\) left and right singular vectors and are kept fixed. The diagonal matrix \(D\) and error matrix \(E\) are trainable. A sparsity structure can be adapted to \(E\) to reduce computational cost of training a large number of parameters.

Optimization using Momentum with Gradient Descent

Suppose that we have a loss function \(L(\theta)\) that we want to minimize with respect to \(\theta\). Typical gradient descent updates look like:

\[ \theta^{(t+1)} = \theta^{(t)} - \alpha \nabla L(\theta^{(t)}) \]

Theoretically, under suitably small step sizes (i.e., \(\alpha\)), gradient descent always improves the objective, and converges always to a local minimum. Furthermore, with some additional assumptions, the rate of convergence can be proven to be exponential.

However, in many practical scenarios, you will see that the drop in objective value is significant at first, but becomes lesser and lesser as things approach minima: and the pace of convergence slows down very much. This happens because near the minima, we would have \(\nabla L(\theta) \approx 0\), which essentially says that the typical gradient descent will only take very timid steps. But imagine you are going down the hill (the most common analogue how you would describe a gradient descent algorithm) by taking the steepest road, and you are now near the foot of the hill. Would you still look for the steepest road around there, or would you continue down the same way? The momentum says that you can use the previously computed gradients (which essentially gives you some direction where you came from) to help your descent steps navigate the way. This idea is summarized into a moving average type formula:

\[ \theta^{(t+1)} = \theta^{(t)} - \alpha \nabla L(\theta^{(t)}) - \alpha \sum_{k=1}^t \beta^k \nabla L(\theta^{(t-k)}) \]

At this point, you may be concerned with the fact that implementing this rule will require one to store all the previously computed gradients, i.e., \(\nabla L(\theta^{(t-k)})\) for \(k = 1, 2, \dots, t\) which can be very challenging and quickly run into memory issues. However, simple algebraic calculations can reduce the above daunting equation into two simpler nice equations to avoid this problem:

\[ \begin{align*} z^{(t+1)} & = \beta z^{(t)} + \nabla L(\theta^{(t)})\\ \theta^{(t+1)} & = \theta^{(t)} - \alpha z^{(t+1)} \end{align*} \]

This is essentially the momentum trick. A nice visualization along with a detailed example is available by Goh (2017) on this topic.

Gradient Accumulation

Gradient accumulation is a simple technique by which you can perform neural network training using smaller batches but effectively get the benefit of using a bigger batch size.

In standard training, you might want a batch size of 64 for stable convergence. However, loading 64 complex examples (like high-res images or long text sequences) into your GPU’s VRAM at once might cause it to crash. You are forced to use a smaller batch size (e.g., 8), but this can make your gradient updates “noisy” and unstable, leading to poor training performance.

Gradient accumulation solves this by breaking the large batch down but deferring the update step. Instead of updating the model weights after every small batch of 8, you run the small batch, calculate the gradients, and add them to a “bucket” of gradients. You repeat this \(8\) times (\(8\) batches \(\times\) \(8\) samples = \(64\) samples). Only after the \(8\)-th small batch do you actually update the model weights using the total accumulated gradients. A pytorch implementation of this would look like this:

accumulation_steps = 8 # Define how many steps to wait

for i, (data, label) in enumerate(loader):

output = model(data) # Forward

loss = criterion(output, label)

loss = loss / accumulation_steps # Normalize loss to account for the accumulation

loss.backward() # Backward (grads are added to existing grads)

# Only update weights every 4 steps

if (i + 1) % accumulation_steps == 0:

optimizer.step() # Update weights using accumulated grads

optimizer.zero_grad() # Clear gradsTopics

Model Parallelism

Dropout Layers Discussion

Knowledge Distillation

Activation Pruning

ML Models Testing + Deployment Strategy

Cross-validation Techniques

Human Labelling for Baselining

Leaky Variables

Feature Engineering Techniques

- Cyclical Features

- Categorical Data Encoding Techniques

Feature Importance

Talk about Predictive Power Score

Identify Drift using Proxy Labelling

Model Simplification

How to convert a random forest model to a single decision tree?

Acknowledgements

Many materials covered here are taken from the website by Chawla (2025).